Designing Better Health Visiting Support: Listening to Mothers’ Voices on Perinatal Mental Health

A co-designed workshop with mothers facing perinatal mental health challenges reveals vital insights for creating more compassionate, proactive, and supportive health visiting services. Read more in Vedika Lall’s blog below.

At Care City, we believe that better healthcare starts with better conversations — ones built on care, compassion, and genuine collaboration.

This workshop was part of a research study funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The study, titled “Health visiting for families facing adversity,” is led by Professor Jenny Woodman at UCL, and aims to understand how health visiting can best support families experiencing challenges such as maternal mental health struggles. You can read more about the study in the published study protocol on BMJ Open, where this workshop is one of the four outlined under “Patient and public involvement.”

As part of this, UCL commissioned Care City to explore how health visitors can better support mothers facing perinatal mental health challenges. At Care City, we place communities at the heart of our design and innovation work, recognising that lived experience is a vital source of expertise. This collaboration brought together UCL’s research strengths, through the Thomas Coram Research Unit and led by Dr Alison Lamont and Dr Louise McGrath Lone, with our hands-on experience in designing with communities — ensuring solutions are shaped by those they are intended to support.

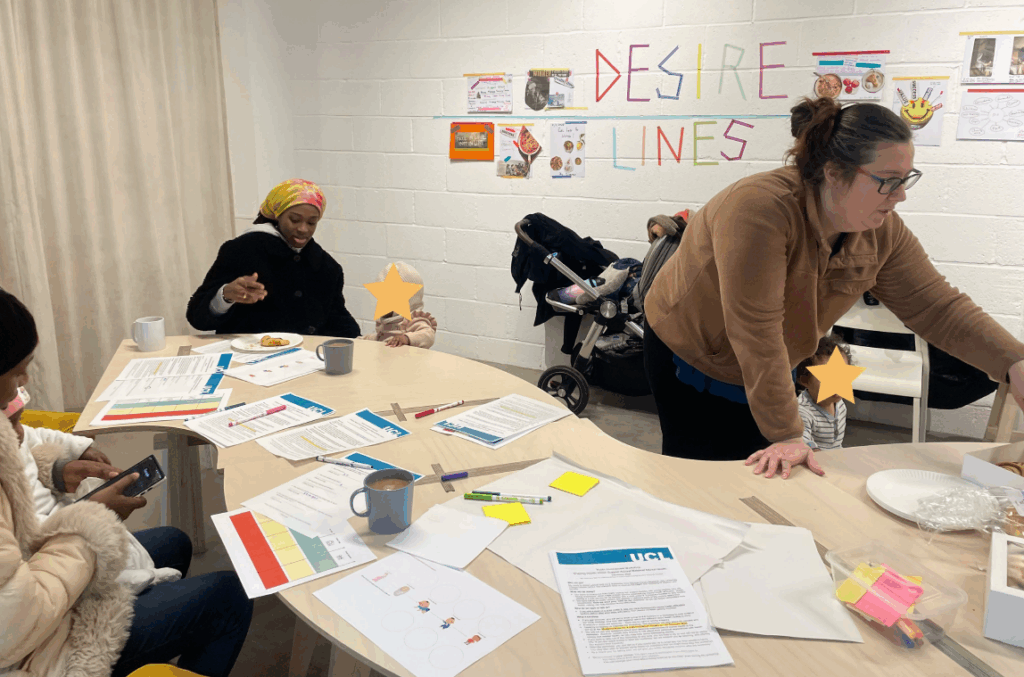

As part of the project, we co-designed a trauma-informed workshop where mothers with lived experience of perinatal mental health challenges were invited to share their views. The workshop took place at the Women’s Museum in Barking in February 2025 and involved small group discussions, creative activities, and collaborative reflection. Care City supported the organisation and facilitation of the workshop, helping to create a safe, welcoming environment where emotional safety, consent and participation were prioritised.

The workshop was designed around open, creative activities that helped mothers share their experiences in ways that felt comfortable and empowering. This included human-centred design focussing on building solutions around people’s real lives, ensuring what we design is genuinely useful, respectful, and supportive. And feminist design which goes further by actively challenging traditional power imbalances — many of whom had experienced dismissal, uncertainty, or fear in healthcare settings — to lead the conversation.

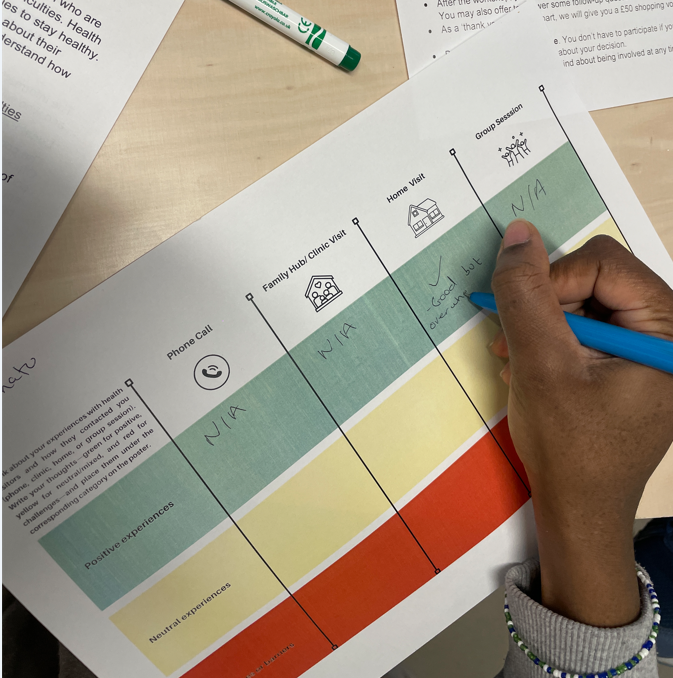

Together, we explored two key questions:

- Where do health visiting contacts happen, and why does the setting matter for mental health and support?

- When is mental health support needed most, and how well do health visiting services meet those needs?

By working this way, we were able to uncover insights that might otherwise have been missed. Engaging mothers through creative, non-judgmental methods revealed gaps in the system — but also showed where small, meaningful changes could make a real difference.

Mothers told us what’s missing — and what could make a real difference

1. Mental health support is needed earlier and more consistently.

Many mothers experienced anxiety and depression in the early months after birth but had little to no follow-up from health visitors beyond initial checks. Mothers wanted early and regular mental health check-ins to be part of the essential health visiting service, rather than being optional.

2. Reactive support leaves mothers feeling isolated.

Support often only came after a crisis point, if at all. Mothers called for proactive outreach — regular emotional check-ins without needing to ask for help first.

3. Signposting is not enough — active support is needed.

Being handed helpline numbers without real conversation made mothers feel dismissed. Mothers wanted health visitors to offer direct emotional support, not just referrals.

4. Clearer communication about what support is available would ease anxiety.

Many mothers didn’t know what to expect from health visiting services, when visits would happen, or what mental health help they could ask for. Clear, upfront communication would reduce uncertainty and stress.

5. Continuity and trust are critical for mental health support.

Seeing different health visitors each time, rushed visits, or cancellations made it hard for mothers to open up about mental health struggles. Building trust through continuity and more personal, unhurried visits could help mothers feel safer and more supported.

How Care City designs with communities: A framework in action

At Care City, the majority of our work is designed with communities and that’s why we’re developing an innovative framework for working with communities that goes beyond traditional consultation.This approach is helping us build more trusting partnerships and create services that genuinely respond to people’s real needs , like our recent work alongside perinatal mothers to reimagine health visiting support.

1. Recognising lived experience as expertise

We treated mothers not just as service users, but as experts. Their insights, resilience, and lived experiences were essential to identifying gaps and shaping on how health visitors can best support mothers’ mental health.

2. Meeting women where they are

We made it easy for mothers to share their experiences on their own terms — through creative activities, open conversations, and flexible formats that respected their physical and emotional needs.

3. Emotional safety first

Emotional well-being came before everything else. We built in pause points, clear consent processes, and options for participants to opt out or rejoin in ways that felt safe and supportive.

4. Designing for emotional realities

We recognised that emotions like anxiety, fear, and exhaustion aren’t just background noise — they shape how women experience care. Our designs responded directly to these emotional states, aiming to reduce stress, uncertainty, and burden.

5. Co-creation, not consultation

Mothers were involved as co-designers, not just consulted after decisions were made. They actively shaped the activities, discussed ideas, and helped generate real-world recommendations for change.

6. Stories as data, action as responsibility

We treated stories as valid evidence, not anecdotes. We also made sure mothers could see how their contributions influenced the findings — creating clear feedback loops that turned personal experiences into shared ownership of the change process.

To make the space feel welcoming and supportive, we offered free daycare, coffee, and plenty of cake — because good conversations (and good ideas) need good support. Being able to bring their children and have help entertaining them during the session made it possible for mums to actually take part. For a workshop designed with mothers in mind, this kind of practical support wasn’t just helpful — it was essential.

“Working with Care City for this workshop has enabled us to connect directly with mothers in the local community who have experienced mental health difficulties, so that we could hear their thoughts on our research findings so far. Vedika, Julie and the CareCity team have been brilliant at designing a supportive, facilitative environment and bringing together mums and scaffolding conversations around mental health and health visiting. Thank you!”

Dr Alison Lamont

At Care City, we’re proud to work in ways that put people’s real experiences at the heart of design. If you’re interested in exploring how we can work together — whether it’s rethinking services, co-designing new solutions, or building more supportive systems for women — we’d love to hear from you.